When the coronavirus hit Canada in March, the British Columbia Teachers Federation realized they had a problem on their hands.

Their convention was coming up in May, and it could no longer happen in person.

Jason Dewolfe, an assistant director at the BCTF, was among those tasked with a challenge: organize the convention online. After asking around, he discovered no union had tried it yet.

“We know that an in-person convention is the best fit every time, but it just wasn’t an option,” he told Campaign Gears. “The important thing for us was to try to match the feel and cultural elements, and ensure that members could control the process.”

They would need to pull off a virtual meeting with 650 registered delegates while trying to replicate the democratic features of a convention: pro and con mics, points of order from the floor, a cascade of amendments upon amendments on the fly, quickly changing speakers lists, microphones controlled by chairs, and secret ballots.

The solution they landed on was an interesting mix of high and low tech.

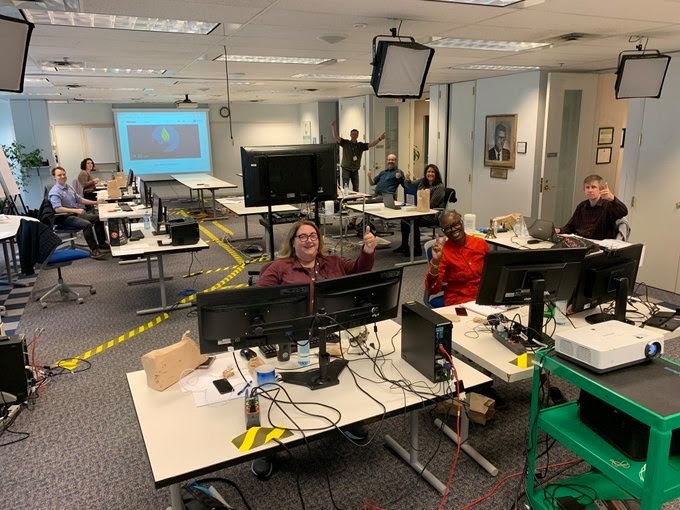

The BCTF building in Vancouver was opened up for the first time since the pandemic started. One room was chosen — this would be the central command, the hub from which the whole operation was coordinated. They began assembling a team that would coordinate the virtual convention.

Every member of the team that would work on-site had a back-up person ready off-site – in case somebody got sick, they would need a replacement. A custodial team cleaned the room thoroughly every night. There were first-aid attendants on hand.

The organizers picked three main tech platforms.

They used Youtube for live streaming (with closed captioning), for showing the resolutions on the floor, and for what normally appears on the screens during an annual general meeting or convention.

But they decided to turn off the sound on Youtube, and had people listening in by telephone to ensure people wouldn’t tune out. Using a Broadnet Telephone town hall, they were able to manage the speakers’ lists and allow delegates to address the floor.

And finally, they used the SimplyVoting app for elections and voting on convention business.

Because these different platforms aren’t integrated, the team in command central would have to rapidly communicate with one another to ensure things flowed as smoothly as possible.

This required several teams of people. Some were off-site, like the team managing tech, helping members stickhandle web issues, or deal with resolutions.

But most were in the room. There were separate teams to help identify delegates, to manage the Simply Voting, to work as phone operators, to manage a speakers list, and to manage the live stream.

All the chairs of the meeting were in the room, using a single telephone line to speak to the 650 members listening in. “The only room that was big enough to accommodate everyone turned out to only have a single phone line,” Dewolfe says. “And we had to use it on speakerphone, because we wouldn’t be able to wipe down the handset every time someone new needed to use it.”

That meant that others in the room couldn’t shout or even talk, because then the entire convention would overhear them.

This led to some comical problem-solving.

“We had hand signals,” Dewolfe says. “We also put the phone on a library cart, and we had one person responsible for wheeling it in front of whichever chair needed the phone.”

On one occasion, as it was being wheeled around, the phone got dropped, and the connection was lost. For a minute, the convention was plunged into a muzak session.

While working out such kinks, Dewolfe says the first day of the convention was slow, but as it went on, it felt much more like usual conventions.

Across the province, there were some pockets of teachers who were able to gather in the same place, while observing the distancing measures. Other pockets of teachers set up their own zoom and group chats, simulating hallway conversations.

The technological set-up sometimes got used in fun, unexpected ways, Dewolfe says.

As one of the member chairs was telling particularly cheesy jokes, the tech support line started to light up. It turned out it was members calling in with additional jokes of their own.

Pulling off a speakers list

This was probably the most difficult element of a convention to reproduce in an online setting.

Here’s how it worked.

During the convention business, everyone was on phone, using the telephone town hall software to listen in.

If a delegate wanted to speak, they would hit *3 — this would connect them to an operator who would ask them their intention.

The operator in the central command room would write down that information, and then pass it to another staff member responsible for maintaining a speaker’s list.

If, as an example, they were appealing the ruling of the chair, they would get bumped immediately to the top of the list.

The delegate would then have the chance to voice their appeal.

Dewolfe has no doubt the technologies will evolve over the coming months, but overall deemed the BCTF experiment a success.

One of his personal highlights was the moment they succeeded in replicating a old union tradition.

When a member calling in on the townhall system announced it was their first convention, all those in the central command room spontaneously broke their usual silence and erupted into applause that resounded over the phone line, honouring the first-time delegate in the way it is always done.